A Millennia Ago

Geologically speaking, the Colossal Cave system is a relative newcomer to the neighborhood. About 300 million years ago much of the American Southwest was covered by a vast sea populated by giant sharks, tetrapods and other primitive amphibians. Eventually the waters receded. Organic material left behind dried out and was compressed to form the limestone you see today. Then 80 million years ago the heaving earth thrust limestone and granite together to create new landforms such as the Rincon Mountains where Colossal Cave is located. After eons of water erosion, the Cave reached a dry state, and today Colossal Cave is one of the largest dry caves in north America — a snapshot of the formations as they were created millennia ago.

Circa 900 AD

In spite of the desert’s forbidding nature, life has survived, and even thrived here. The earliest inhabitants of the region were the Hohokam, a prehistoric culture who called Arizona home for more than 1,200 years. Subsistence farming was made possible through their highly advanced network of irrigation canals that at its apex stretched more than 150 miles. Archeologists have discovered evidence that the Hohokam used the Cave as temporary shelter as early as 900AD.

The Wild West

Westward expansion in the 19th century attracted ranchers and homesteaders. Solomon Lick was among them. He rediscovered the Cave in 1879 while searching for stray cattle. The Cave became legendary when train robbers used it as a hideout after pulling a job. But there were riches inside that the robbers did not appreciate: Bat guano. As fertilizer it was a valuable commodity. In 1905 a tunnel was excavated to mine the guano until it ran out. Next, a boom in Cave tourism was about to begin.

The Bandits of Colossal Cave

Even before tours were taken in Colossal Cave in the late teens and early twenties, it was reputed to have been a bandits’ hideout, and one or another version of what we term our “Bandit Legend” has been told. It took on a life of its own, and while certain details and embellishments have been added and subtracted over the years, the basic story has remained pretty constant:

In 1884, four men held up a mail train near Pantano, a tiny town east of Tucson and just south of Colossal Cave, and got away with $72,000 in gold and currency. They hightailed it into the Rincon Mountains. Sheriff Bob Leatherwood got a posse together and trailed the bandits to a hole in a mountainside—a cave entrance. When the Sheriff stuck his head in, he was greeted by gunfire, so he decided the best thing to do was to starve the bandits out. He sat in front of that hole for two weeks, till one day a deputy came riding up to tell him that four men were whooping it up in the Corner Saloon in Willcox—that’s about 70 miles from the Cave—throwing gold around and bragging about how they’d left the Pima County Sheriff sitting in front of a cave in the middle of the desert while they took a back way out.

In 1884, four men held up a mail train near Pantano, a tiny town east of Tucson and just south of Colossal Cave…

The posse took off for Willcox and cornered the men in the saloon. In the gunfight that followed, three of the men were killed. The fourth, named Phil Carver, was arrested and sentenced to twenty-eight years in the Federal prison at Yuma. The Cave, of course, was thoroughly explored, and the back entrance and bandits’ lair found: the remains of a campfire, food, clothes, all there—but not a trace of the $72,000.

Phil Carver served eighteen years and, upon his release, came right to Tucson. Sheriff Leatherwood, who was still in office, had him followed relentlessly, but Carver gave his trackers the slip and headed for Colossal Cave. By the time a posse got there, he was gone. All that remained—slit open and abandoned in a hole in the Cave—were several empty mailbags.

What the Legend really is, is a mosaic made up of fragments of several actual occurrences. Here are the true tales as far as we know them…

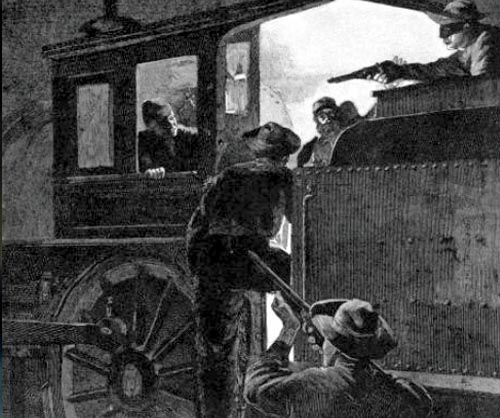

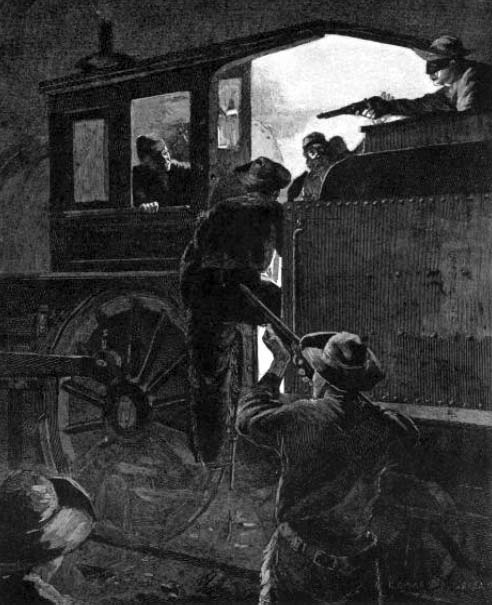

April 27, 1887: In the darkness before moonrise, as westbound Southern Pacific passenger Train 20 headed down the track from Pantano toward Tucson, was ambushed by four masked men. They brought it to a halt by setting off explosives on the tracks, signaling with a red train lantern, and shooting the cars full of holes. As Wells Fargo Express messenger Charles F. Smith barricaded himself behind the locked door of the express car, the bandits forced the engineer to carry a heavy explosive back to the express car and tell Smith to unlock the safe and get out or they would both be blown to kingdom come. Smith did.

The bandits uncoupled the engine, express, and mail cars from the rest of the train, hopped on the engine, and steamed toward Tucson, leaving the passenger cars and crew behind. They ransacked the express and mail cars, and a few miles from town, they got off, put the locomotive in reverse, and sent it back toward Pantano while they took off into the desert. Although they got away with several thousand dollars, they missed thousands more which messenger Smith had hidden in the stove in the express car.

The Legend is really a mosaic. It is made up of fragments of several actual occurrences.

In the days before the robbery, the bandits made Mountain Springs Ranch, known today as La Posta Quemada Ranch, their hideout.

Three more train robberies took place on the Southern Pacific line in Texas between April and August.

Then on August 10, 1887, same train, same place, same time of night, Express messenger Smith in the express car, here we go again. Two men stopped the train by the same method—shooting off explosives and firing into the cars. One shot clipped off half the engineer’s mustache. This time, the bandits booby-trapped the track by throwing a switch. The locomotive thundered off the rails and overturned, along with the coal-tender. As this was at the top of a fifty-foot high embankment, it was fortunate that the railroad bed was wide enough so the cars didn’t go over the edge. The fireman jumped into the top of a big mesquite as the engine went over, but the engineer didn’t have time to follow, and rode it down till he could climb out the window and roll to the bottom of the embankment.

Meanwhile, the robbers ordered messenger Smith to open up the express car. When he refused, they blew a hole in the door, and recognizing him, one said, “Smithy, the stove racket don’t go this time.” When he refused to open the safe, they pistol-whipped him till he saw reason. They went through the safe and hightailed it into the Rincon Mountains with U.S. currency and gold.

The posses tracked them from there to a very large cave, known then as Five-Mile Cave at Mountain Springs. Today we call it Colossal Cave.

Posses consisting of sheriffs and deputies, as well as cavalry, Yuma Indian trackers, and even Marshal Virgil Earp, searched for over a week. They discovered that the bandits had again used Mountain Springs Ranch as a rest stop, and in fact all the tracking parties made it their headquarters. They found a small shelter cave near here in the Park, which the bandits had used as a hideout. But the robbers were gone, leaving behind food, clothing, some coins and jewelry, the remains of a campfire, but no loot. The posses tracked them from there to a very large cave, known then as Five-Mile Cave at Mountain Springs. Today we call it Colossal Cave. Here the bandits hid out for several more days, and then taking advantage of the extremely rocky terrain and an absolute gully-washer of a rainstorm, they escaped completely.

Two months later, October 17, 1887, well after dark, an eastbound passenger train train was held up near El Paso by two men. The robbers went straight to the express car and blew the door open. Express messenger Smith (a different one, J. Ernest Smith, this time) realized what was happening and had already snuffed out the lamp. He left his gun on the floor in the doorway and dropped from the car, intending to land on one of the robbers and slug him and then turn back for his gun. Instead, he found himself at gunpoint. When the bandits wanted a light in the express car, Smith volunteered to climb in and light it. He put his hands on the car floor, grabbed his gun, and shot one of the robbers through the heart.

The other robber picked up his dead buddy, carried him ahead to the engine, and ordered the fireman to put him on board. During this confusion, messenger Smith took aim and shot the second robber, who staggered off. He was found dead the next morning less than fifty feet away.

It turned out that El Paso was the headquarters of a gang of train robbers who made their hideout in some caves near that city, probably those now known as the Aztec Caves in Franklin Mountain State Park.

For that robbery, he was sentenced to five years in Yuma prison.

Ultimately, four men were brought to trial—two were acquitted, two were convicted.

Of the two convicted, George Green of El Paso was the chief witness regarding the April robbery. He testified that the two bandits who were killed trying to rob the El Paso train were part of the gang which pulled off both Pantano robberies. And although Green (a.k.a. George Wills) said he was not involved in any but the April robbery, there were reports that he “plea-bargained” and testified against the others in return for being tried for just the one robbery. For that robbery, he was sentenced to five years in Yuma prison. He served only five months there before he was transferred to the Penitentiary in Ohio for the remainder of his sentence. We have no further information about him.

The other man who was convicted was J.M. “Doc” Smart, subsequently pardoned on appeal by no less than President Benjamin Harrison.

As to the money, to this day, no one knows how much was stolen or what happened to it. Wells Fargo was notoriously tight-lipped about revealing how much was ever lost in any robbery of which they were a victim, no doubt because they feared loss of confidence by their customers. Depending on which robbery you’re talking about, figures ranging from $3,000 to $70,000 missing were published at the time.

Is there gold hidden in Colossal Cave?

George Green said he saw considerable sums being passed around among his compadres after the April robbery. Wells Fargo later said that the amount which messenger Charles Smith hid in the stove was $30,000. This gives rise to the question, how much was there to begin with? In the August robbery, Wells Fargo credited Smith with scattering a “heavy consignment of gold” throughout the express car, and said that had mitigated how much was taken. Well, how much was there, and how muchwas taken? Is there gold hidden in Colossal Cave?

Is it in our best interests to say?

Another tale which may have contributed to our Bandit Legend has to do with three Tucson gamblers, Gibson, Murphy, and Moyer, who had a feud with another gambler named Levy. One day in 1882, they called Levy out of the Cosmopolitan Saloon and each took a shot at him. They hightailed it into the Rincons and hid in Colossal Cave for a while before decamping to the Catalinas and then the Galliuros. They were captured and put in Pima County jail. Next thing you know, they were reported to have tricked and overpowered their jailer, leaving him tied up and gagged in their cell. They set six other prisoners free, and all escaped.

Ultimately, they were recaptured and brought to trial on murder charges. Murphy and Moyer were found guilty, while Gibson was acquitted on the grounds that Levy was already dead when Gibson’s bullet hit him!

Two interesting points

1) The jailer, George Cooler, within a month of the jailbreak, pled guilty to letting the prisoners go.

2) George Cooler was a member of the “original” exploring party, the one which explored the Cave in 1879.

© E. Lendell Cockrum, M. K. Maierhauser

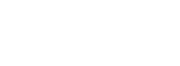

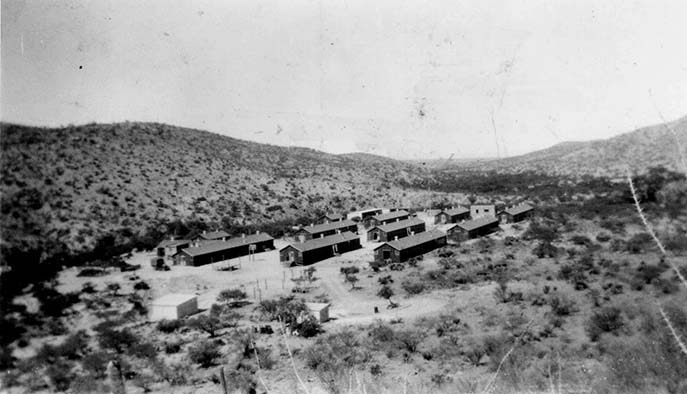

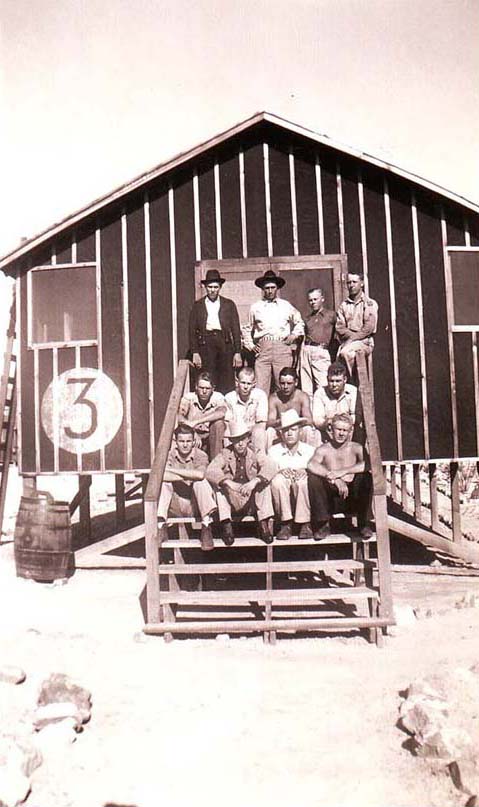

Civilian Conservation Corps

Just as awareness of the Cave began to grow disaster struck: The Great Depression. Ironically this economic catastrophe triggered the Park’s growth. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was created to provide jobs to the unemployed in public works projects. Early development of the Park was done by the CCC. Their initial efforts included building the Park roads along with lighting and walkways in the Cave. The stone building that is now home to the Café and Cave Shop was built by the CCC. Today Colossal Cave Mountain Park is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Civilian Conservation Corps

The CCC was created in 1933 “for the relief of unemployment through the performance of useful public work, and for other purposes”. One of the most successful New Deal programs of the Great Depression, it existed less than ten years, but left a legacy of strong handsome roads, bridges, and buildings throughout the United States.

Colossal Cave Mountain Park owes an enormous debt to the Civilian Conservation Corps for its handsome headquarters buildings, to say nothing of the installation of the lighting, walkways, and handrails in the Cave. The CCC also laid out the Park roads and built restrooms in the Park (since replaced, although the buildings still stand) as well as the ramada in La Selvilla picnic area.

The CCC was created in 1933 “for the relief of unemployment through the performance of useful public work, and for other purposes.”

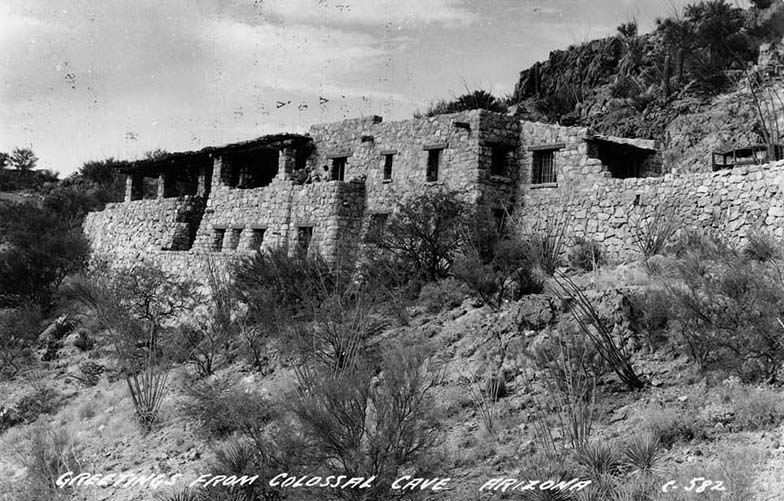

Camp SP-10-A— the Park’s camp— had its headquarters at La Posta Quemada Ranch, now part of the Park. The camp was manned by two companies. The first one, Company 858, was housed in tents on the Ranch from May, 1934 to October, 1935. They started the work in the Cave and constructed the Army barracks buildings that the second company lived in.

It was the second group, Company 2851, who built the stone buildings (now listed on the National Register of Historic Places) and finished the work in the Cave and the greater Park.

And they had a newsletter.

The Colossal Cave Chronicle, edited by Vincent Suarez, started January 31, 1936 and ran for a month or two. It became The Cave Man, and was still edited by Vincent Suarez for the next several months. He was followed by James M. Lamb for about five months, and finally Charles Scott took it for at least seven months and eventually changed the name to The Colossal Caveman.

By the way, the “birthday” issue of The Cave Man noted: “August 19th [1936] will mark twelve months of progress for Company 2851 Colossal Cave, Vail Arizona. The men consider the work in and around the cave as the most interesting project in the Tucson District. The esteem by which the enrollee’s hold this camp is clearly shown by the fact the company strength of 180 is the largest in the Tucson District.”

Beans, Beans and more Beans…

A taste (in one case, almost literally) of the newsletters follows….

Beans, Beans, and More Beans

There are three kinds of beans: those we had yesterday, those we are having today, and those we will have tomorrow. In addition to that, some beans are white, some are brown, and some are spotted.

Beans may be served in seven ways: (1) plain beans, (2) fancy beans, (3) bean salad, (4) bean soup, (5) beans with chili, (6) beans without chili, and (7) bean sandwiches. We have yet to see them served with pancakes. We don’t have beans for breakfast.

Beans are very healthful. They contain calories, vitamins, carbohydrates, and lots of other funny things. We are lucky that our cooks know seven ways to cook beans, in some camps they always serve them baked. [Volume 1, Number 1, January 31, 1936, Vincent Suarez, editor.]

SP-10-A to Celebrate First Anniversary

The local camp will light its first birthday candle August 17th which will mark twelve months of progress for Company 2851.

Enrollees Battle Conflagration

Eleven members of this camp extinguished a forest fire in the Rincon Park area August 3rd after twenty hours of courageous fighting, continuously battling with little rest. The blaze marked the initial forest fire in this area but it was successfully quelled… An article lauding the men’s work appeared in the Arizona Daily Star…

Personals

Jack Chenault and Henry Schafer returned recently from Bracketsville, Texas, after an unsuccessful attempt to secure employment. They report the El Paso prison pea farm isn’t quite up to SP-10-A standards.

Morning Exercise Inaugurated

“One-two-three relax” is again a familiar sound as enrollees nimbly exercise those stiff joints each morning prior to breakfast.

The value of calisthenics can’t be overly rated so in the future morning exercises will be held five times weekly.

However, some of the not overly energetic believe that setting-down exercises during reveille would get more response from the boys. [Volume 1, No. 8, August 15, 1936, James M. Lamb, Editor.]